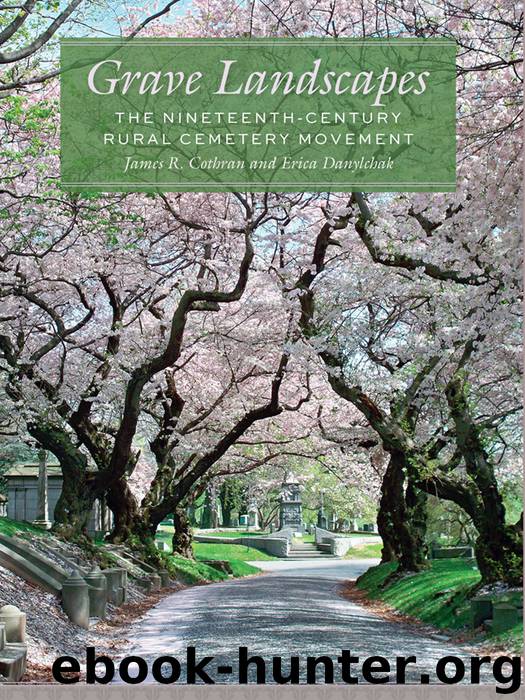

Grave Landscapes by James R. Cothran Erica Danylchak

Author:James R. Cothran,Erica Danylchak

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University of South Carolina Press

Published: 2017-04-29T04:00:00+00:00

120. Iron Fencing. From Green-Wood Illustrated, 1847, Danylchak collection.

121. Family plot encompassed by stone curbing, Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York. Photograph by Erica Danylchak, 2013.

Family (or group) plots were often bordered by stone curbing after fencing fell into disfavor. The area within the curbing was commonly built up with good soil and was, therefore, higher than the surrounding ground, visually elevating the stature of the family plot. One or more steps generally rose up from the adjacent path or avenue. Stone curbing was usually engraved with the associated family name and lot number. At Mount Auburn, the first curbing was installed in 1858. By the 1870s and 1880s, however, even this less obtrusive form of lot enclosure lost favor at Mount Auburn.

Garden furniture and vases also became common adornments in the family plot. The furniture was functional, providing a place for family members to rest during visits to the grave. These personalized embellishments enabled the family to domesticate their cemetery space, exemplifying the dramatic change in the role of burial grounds for survivors. Early in the rural cemetery movement, cemetery corporations encouraged such additions. An 1852 guide to Laurel Hill Cemetery, for example, recommended the work of a local firm, Woods’ Iron Works, which produced garden and arbor chairs and settees. These embellishments, the guide stated, “generally combine lightness, strength and stability. Some of these articles are of superior execution; the decorations, principally foliage and flowers, are designed with great force and spirit, and are reproduced with truthfulness of effect. These chairs and settees form agreeable and appropriate adornments to a family burial lot.”36

In the early years of the rural cemetery movement, lot holders were responsible for choosing monuments and enclosures, arranging for plantings within the lot, adding decorative embellishments, and maintaining the features installed. Although some cemetery associations did provide guidelines for lot improvements, the family lots of early rural cemeteries were highly individualistic and varied. Over time, problems developed as a result of the autonomy given to lot holders. Cemetery associations observed, for example, that not all lots were being properly maintained. Although reluctant to assume responsibility for the private property of family lots, in the early 1840s, Mount Auburn’s board of directors developed the idea for a trust that would provide funds for repairs within these lots. Other cemeteries soon followed Mount Auburn’s lead. The freedom given to lot holders had also led to an overpowering multiplicity of ornamentation that marred the naturalistic landscape of the rural cemetery ideal. Gradually, stricter regulations were enacted on lot holders. Eventually, however, the rural cemetery model underwent a significant, and perhaps inevitable, change under the direction of the visionary superintendent at Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati.

Individual Graves

The new cemetery enterprises were praised as being egalitarian. Family lots were generally available to members of any religious or ethnic group. In the North, burial space was often open to African American citizens as well. However, the cost of family lots was prohibitive for many American families. In 1846, the smallest family lot at Green-Wood Cemetery, measuring three hundred square feet, cost eighty dollars.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Kathy Andrews Collection by Kathy Andrews(11793)

The remains of the day by Kazuo Ishiguro(8947)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5165)

Paper Towns by Green John(5163)

The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson(5065)

Industrial Automation from Scratch: A hands-on guide to using sensors, actuators, PLCs, HMIs, and SCADA to automate industrial processes by Olushola Akande(5038)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4280)

Be in a Treehouse by Pete Nelson(4017)

Never by Ken Follett(3917)

Harry Potter and the Goblet Of Fire by J.K. Rowling(3834)

Goodbye Paradise(3790)

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro(3377)

Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer(3369)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3352)

The Cellar by Natasha Preston(3316)

The Genius of Japanese Carpentry by Azby Brown(3277)

120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade(3245)

Reminders of Him: A Novel by Colleen Hoover(3061)

Drawing Shortcuts: Developing Quick Drawing Skills Using Today's Technology by Leggitt Jim(3057)